Writing System

Last Updated October 20, 2024

Introduction

Signed languages are visual languages that communicate ideas through an ever-changing appearance of the hands according to a grammar structure or syntax. In this article, Sign language (SL) is used to refer to the ever-changing appearance of one's hands relative to one's entire body. The hands change appearance by moving, and being physical objects, follow all the rules of classical mechanics. As a result, writing down a SL is tantamount to writing the rigid body dynamics of the hands and body. However, formal dynamic equations, like many linguistic transcription systems for SLs, are too precise to be practical for writing literature in a SL. Fortunately, modern SLs (e.g., British Sign Language, langue des signes française, or American Sign Language) have distinguishable phonologies that act to simplify the overall dynamics and render them writable.

On this page, we describe the writing system developed and used in the Sign Language Dictionary (SLD). The purpose of this writing system is to allow users to type and search signed language literature in accessible software on widely available electronic devices. The writing system was constructed from the Latin Extended-A Unicode block and contains the following 67 characters:

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZÁÉĆÚÓ

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzáéćúó

-=~/'

American Sign Language (ASL) words are printed in Consolas font, which can be seen in the examples provided on this page.

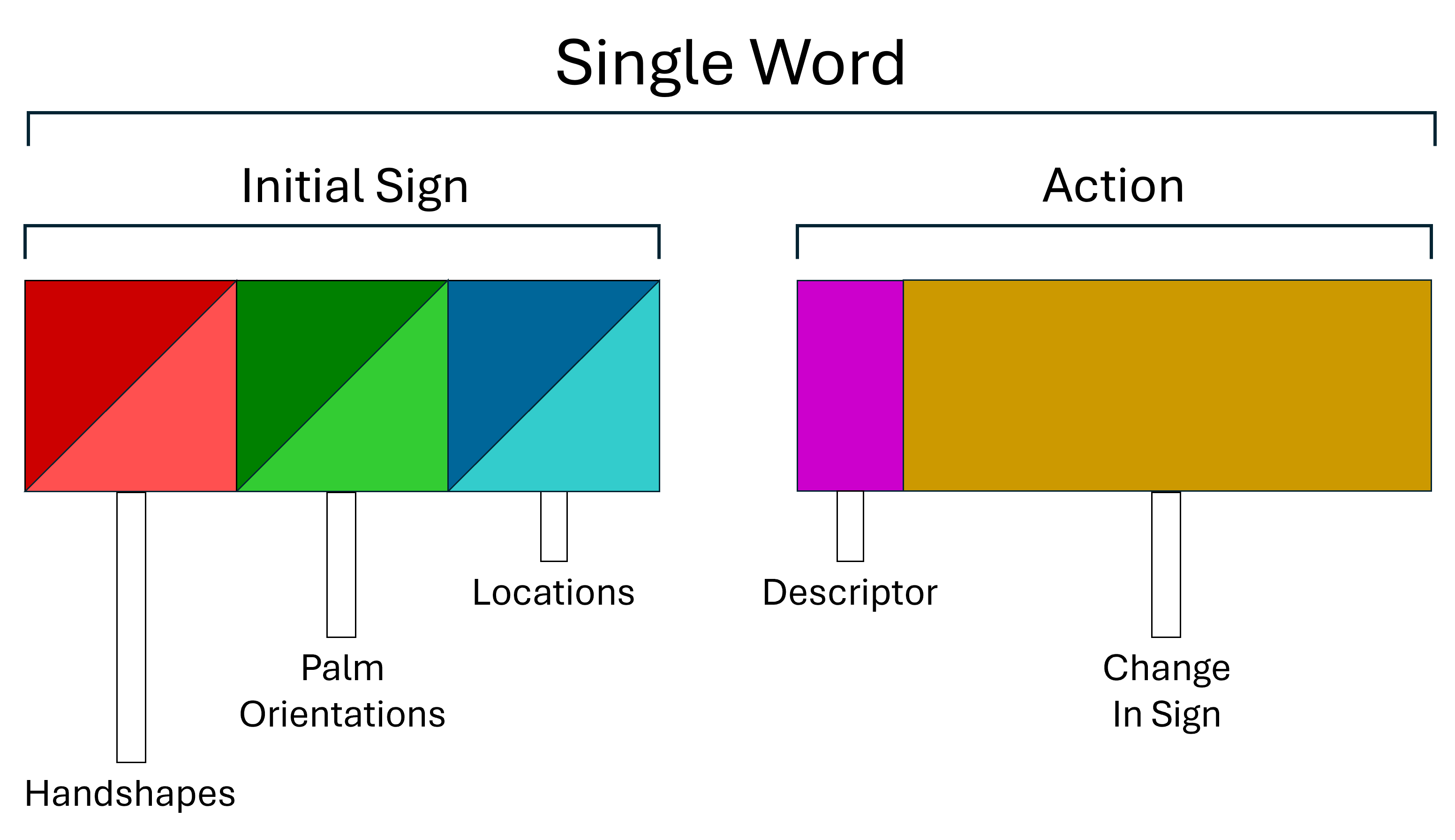

In this writing system, SL words are written in two segments, the initial sign segment and the action segment. The initial sign segment, covered in section 1, refer to the word-initial letters that describe how the word begins its articulation. The action segment, covered in section 2 refers to the word-final letters that describe how that articulation evolves to end the word. The most general word structure has a two-part appearance, where the initial sign segment establishes a background shape for the word and the action comments on that shape.

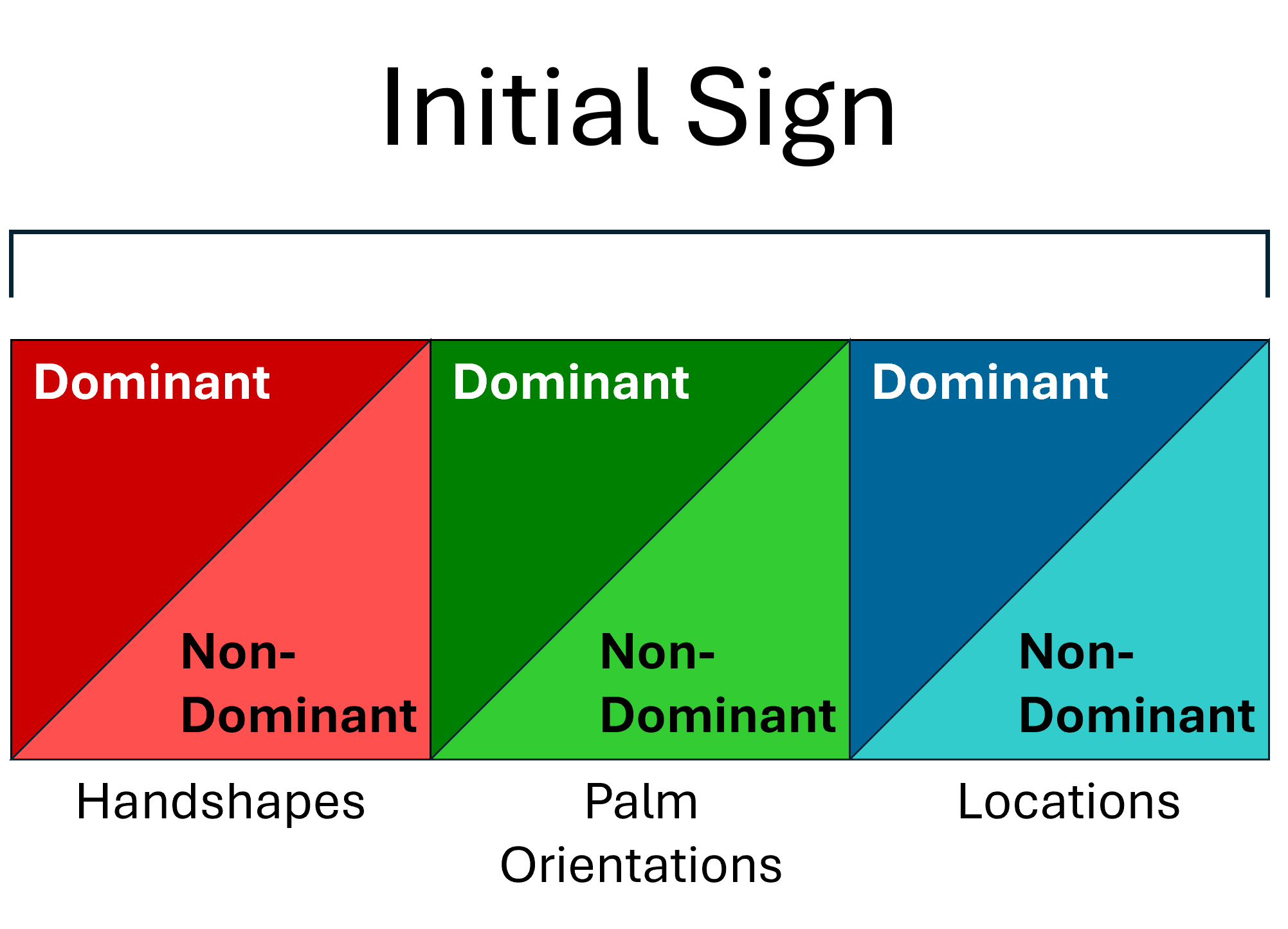

The initial sign segment is written with three parts:

- handshape (section 1.1)

- palm orientation (section 1.2)

- location (section 1.3)

These three parts are written in pairs that refer to the signer's dominant hand and non-dominant hand. The dominant hand corresponds to the hand (right or left) that a person tends to favor when performing certain activities, while the non-dominant hand corresponds to the other hand that can be active or passive in those activities.

We refer to the number of hands used to produce a signed word as handedness, that being either one or two. In signed languages, words produced are either one-handed that use the dominant hand alone, or two-handed that use both dominant and non-dominant hands. The handedness of a word will influence how its initial sign segment is written. This is discussed further in section 1.3.1.

The action segment then completes the spelling of a word and is written with two parts:

- the action descriptor (section 2.1)

- the change in sign (section 2.2 and section 2.3)

The action descriptor describes the frequency, phase, and symmetry of the motion that changes the hand configuration of the initial sign segment. The change in sign describes the type of motion. The following figure illustrates a signed word and its components.

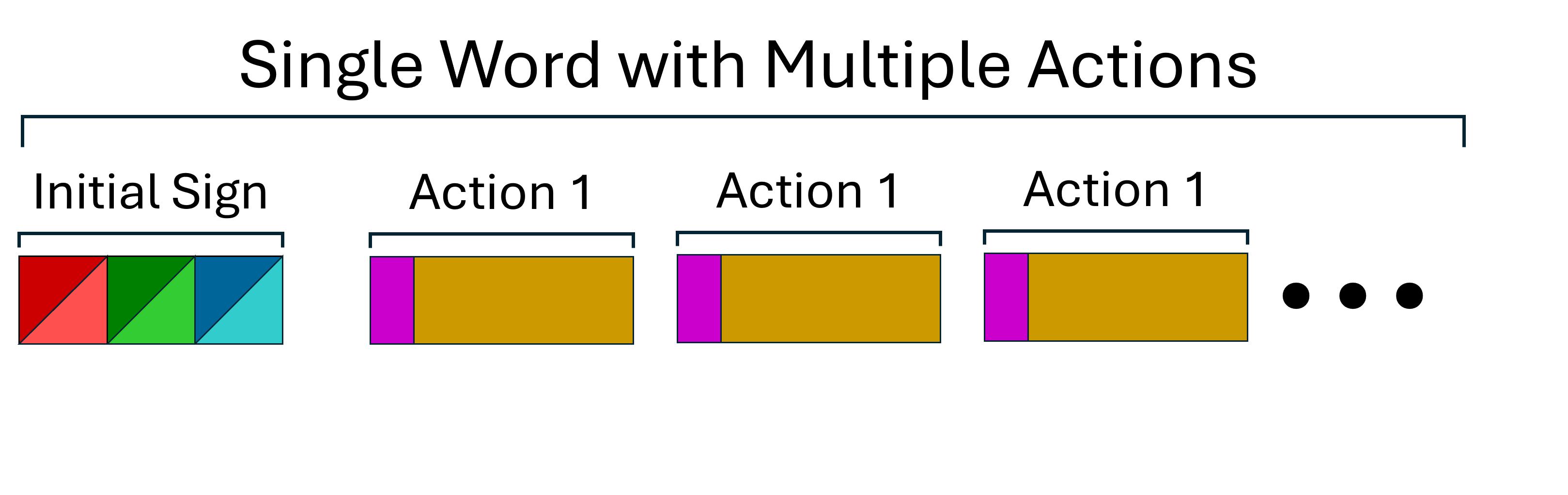

In addition, signed words may have more than one action, which are spelled together as a series. This is discussed in section 3. The diagram below illustrates the structure of a word with multiple actions.

Some signed words may involve simultaneous movements of the two hands. Such motions are spelled as a series of action segments following the initial sign segment. This is discussed in greater detail in section 3.6.

In the following sections, we describe our method for spelling in detail, showing how all the features of a signed word are written. Examples are provided in ASL and each one is accompanied by an italicized English gloss, which comes from source material listed in our Library. We provide descriptions of how the spellings for specific words may be written based on how it is articulated by signers. We largely refrain from discussing the specific meaning of words, since a discussion of signed language semantics is beyond the scope of this page. However, for words having depictive motions, we provide a limited interpretation of their meaning, since we believe some detail of that sort is required for the reader to better visualize what is being represented in the spelling of those words. Nearly all ASL words used in the examples on this page can also be found in the Main ASL Dictionary.

1. The Initial Sign Segment

As mentioned above, the initial sign segment is generally composed of three parts, where each part is written as pair corresponding to the dominant hand and non-dominant hand of the signer, respectively. The following diagram illustrates the structure of the initial sign segment.

In the following subsections, we describe each of those three parts in sequence.

1.1 Handshapes

A handshape refers to a hand's configuration of the fingers and thumb. The initial handshape is the initial configuration of a hand at the beginning of a word. Initial handshapes are spelled as a pair and start the spelling of every word. These handshape pairs refer to the dominant hand and non-dominant hand, respectively. The handshape for a single hand is spelled as a sequence of letters. The first letter in a single handshape identifies the main handshape category. Examples of the main handshape categories are illustrated in the following figure.

![Figure 4. Examples of main handshape categories [s, l, v, w, f, y, h, m, b] with thumb modifier [a]. Figure 4. Examples of main handshape categories [s, l, v, w, f, y, h, m, b] with thumb modifier [a]. Left: [sa] shows thumb extended, all fingers fully flexed. Top row, left to right: [la] shows thumb and index finger extended, pinky, ring, and middle fingers fully flexed; [va] shows thumb extended, index and middle fingers extended and abducted pinky and ring fingers fully flexed; [wa] shows thumb extended, index, middle, and ring fingers extended and abducted, pinky finger fully flexed; [fa] shows the thumb extended, all fingers extended and abducted. Bottom row, left to right: [ya] shows the thumb and pinky finger extended, other fingers fully flexed; [ha] shows the thumb extended, index and middle finger extended and adducted, ring and pinky finger fully flexed; [ma] shows thumb extended, index, middle, and ring finger extended and adducted, pinky finger fully flexed; [ba] shows thumb extended, all fingers extended and adducted.](/static/main/word_structure/Figure_5.png)

A single handshape spelling is on average composed of two to four letters ending in [a, e, c, u, o], but longer spellings are possible. That single handshape sequence of letters describes the configuration of the fingers and the thumb. Specifically, the letters [a, e] describe only the thumb position, and the letters [c, u, o] describe both the thumb and fingers. Examples of their use are illustrated in the following figure.

![Figure 5. Examples of [f] handshapes with thumb modifiers [a, e] and thumb-finger modifiers [c, u, o]. Figure 5. Examples of [f] handshapes with thumb modifiers [a, e] and thumb-finger modifiers [c, u, o]. Left to right: [fa] shows thumb extended and all fingers extended and abducted; [fe] shows thumb flexed and adducted to the palm, all fingers fully extended and abducted; [fsc] shows thumb and index fingers partially flexed towards each other but not in contact, other fingers are extended and abducted; [fsu] shows first knuckle of thumb and index finger flexed, other fingers are extended and abducted; and [fsco] shows thumb and index fingers partially flexed towards each other and in contact, other fingers are extended and abducted.](/static/main/word_structure/Figure_4.png)

There are two additional finger modifier characters [x] and [r]. These additional modifiers only occur with words ending in [a] or [e]. The finger modifier [x] applies to fingers that would otherwise be extended, whereas [r] applies to lone pairs of adducted fingers that would also otherwise be extended.

![Figure 6. Examples of handshapes with finger modifiers [x, r]. Figure 6. Examples of handshapes with finger modifiers [x, r]. Left: handshape [bxe] shows thumb flexed and adducted to the palm, all fingers are flexed at second and third knuckles and abducted. Right: handshape [hre] shows thumb flexed and adducted to the palm, index and middle fingers extended and crossed, ring and pinky fingers fully flexed.](/static/main/word_structure/Figure_6b.png)

Hundreds of different handshape spellings are possible. An in-depth discussion of handshape spellings, the rules for spelling handshapes and animated illustrations of the most common handshapes can be viewed here: Animated Handshape Categories. To view the handshapes and spellings that correspond to the English alphabet, please see our ASL Manual Alphabet page.

An example

Let us first consider the ASL word glossed as example. The two handshapes used in this word are [le] for the dominant hand and [ba] for the non-dominant hand. Thus, the initial sign segment of this ASL word is written as [leba], illustrated by the following figure, and the entire word is written as lebatkitpj=a.

![Figure 7. Handshape examples [le, ba] corresponding to the initial sign segment. Figure 7. Handshape examples [le, ba] corresponding to the initial sign segment. The dominant hand (center-top, red) corresponds to handshape [le] (left), showing thumb flexed and adducted to the palm, index finger fully extended, other fingers fully flexed. The non-dominant hand (center-bottom, pink) corresponds to handshape [ba] (right), showing thumb extended and abducted, all fingers extended and adducted.](/static/main/word_structure/Figure_5b.png)

1.1.1 Using the Thumb

In the handshape of some words, the thumb may be fully extended. In such words the [f], spelled just before the thumb and thumb-finger modifiers characters, signifies that the thumb is fully extended. This spelling distinction is in order to clearly identify configurations that use the thumb to contact the body, to point, or to depict a concept. Examples of these handshapes include: [sfa], [lfa], [vfa], [wfa], [yfa], [hfa], [mfa], and [bfa].

Contact

Contact involving the thumb occurs when the direction of the thumb points into the contact location. A prime example is the ASL word lfábaiaitpj-usj, glossed as later. This word begins its articulation with the thumb of the dominant hand [lfa], pointing to and contacting the palm of the non-dominant hand. The table below lists more examples of words that require a fully extended thumb.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|

| sfáitni=a | girl | one | Inactive |

| lfábaiaitpj-usj | later | two | Inactive |

| yfaak=fj | measure | two | Inactive |

| hfatatefj=ufj-a | hurricane | two | Active |

| vfáitci=xfj | insect | one | Inactive |

| bfaitwi=ufj | donkey | two | Active |

| fáit=ui | mother | one | Inactive |

Pointing

Pointing can occur when the fully extended thumb is used to directly indicate someone or something, as in the ASL word sfáej-st, glossed as myself, where the [sfa] handshape indicates one's self by contacting the [st] chest. Another example is the ASL word sfáleteia=bj, glossed as itself. In this two-handed word, the dominant hand [sfa] contacts the non-dominant hand [le]. Here, the non-dominant hand depicts a person or thing, while the dominant hand indicates it by making contact at the location [bj]. The table below lists more words that point with a fully extended thumb.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|

| sfáej-st | myself | one | Inactive |

| sfáleteia=bj | itself | two | Inactive |

Depiction

Depiction of a concept by the fully extended thumb occurs when the thumb itself is used to represent an object or part of an object. An example of this is the ASL word sfáit=oi, glossed as bar. Here the dominant hand [sfa] depicts a bottle and the thumb as the neck of that bottle. The table below lists more words that have depiction with a fully extended thumb.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|

| sfáit=oi | bar | one | Inactive |

| vfáit=wi | rooster | one | Inactive |

| faiawi-i'j | moose | two | Active |

| lfáat=xfja | gun | one | Inactive |

1.2 Palm Orientations

To describe the orientation of the hand in space, the plane of the hand is described within a Cartesian coordinate system. To do this, the three cardinal axes are labeled using six characters and correspond to six different orientations. These are provided in the following list:

- [i] for upwards

- [k] for downwards

- [a] for forwards

- [e] for backwards

- [j] for outwards (sideways)

- [t] for inwards (sideways)

This system and its corresponding characters are illustrated by the following figure.

![Figure 8. Diagram of the Cartesian coordinate system and corresponding characters. Figure 8. Diagram of the Cartesian coordinate system and corresponding characters. Line-drawing of a human standing with right hand raised with palm facing forward (left), and 3 perpendicular axes (right) labeled [i, k] on the y-axis, [j, t] on the x-axis, and [a, e] on the z-axis.](/static/main/word_structure/Figure_6.png)

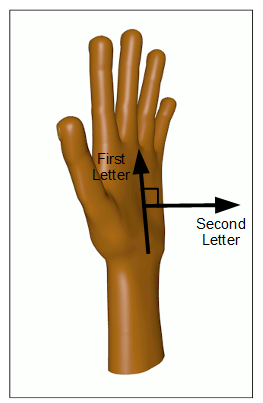

The plane of the hand is then defined by two vectors, each aligned with a different axis. The first vector originates from the wrist and ends at the knuckles. The second vector originates from the palm and points away from it, perpendicular to the first vector. A single palm orientation is then written with two letters that describe the orientation of each of the two vectors. These vectors are illustrated by the following figure.

An example

Let us again consider the ASL word lebatkitpj=a, glossed as example. The first vector of the dominant hand points along the inwards axis [t] and second vector from the palm points along the downwards axis [k]. To represent the non-dominant hand, the coordinate system depicted previously is simply reflected across the signer's body. Thus, the first vector of the signer's non-dominant hand points along the upwards axis [i], whereas the palm's vector points along the inwards axis [t]. Together the two palm orientations form the written pair [tkit], illustrated by the following diagram.

![Figure 7. Handshape examples [le, ba] corresponding to the initial sign segment. Figure 10. Palm orientations [tk, it] corresponding to the initial sign segment. The dominant hand (center-top, dark green) corresponds to vectors for [tk] (left), showing perpendicular right-angle arrows pointing downwards and inwards. The non-dominant hand (center-bottom, light green) corresponds to vectors for [it] (right), showing perpendicular right-angle arrows pointing upwards and inwards.](/static/main/word_structure/Figure_8.png)

1.3 Locations

Locations refer to the starting position of the hands upon initiating articulation of a signed word. While the dominant hand always participates in articulation, with the non-dominant hand participating intermittently, locations are spelled in a way that allows us to represent the location of the dominant hand alone, the non-dominant alone, or both hands together. In the following subsection, 1.3.1, we discuss the structure of spellings that describe the number of hands participating in the articulation of a word and how the hands are located relative to each other. In subsections 1.3.2 and 1.3.3, we discuss these relative locations in more depth.

1.3.1 Placement & Handedness

In general, the handedness of a signed word is described by spelling the handshapes that are involved in producing the word. Therefore, if a word is articulated with two hands, then two handshapes are spelled in the initial sign segment. If a word is articulated with one hand, then one handshape is spelled in the initial sign segment. This contrast in spelling can be seen in the following table by comparing row vii with rows i, iii, and v. For rows i, iii, and v, the handshape pair is spelled [leba], which indicates that the listed ASL words are two-handed. However, row vii has only one handshape [bá] spelled, indicating that this word is one-handed.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | lébatkatfje-te | start | two | dominant | Inactive |

| ii | bbátkaipj-a | clean | two | dominant | Inactive |

| iii | lebáietklj-teluj | day | two | non-dominant | Inactive |

| iv | bbaatsuj=usj | fish | two | non-dominant | Inactive |

| v | lebatkitpj=a | example | two | dominant | Active |

| vi | baat=t | small | two | dominant | Active |

| vii | báieui-a-pj | good | one | dominant | Inactive |

Let us now focus on rows i, iii, and v. The spelling in each of these rows describes two-handed words with the same two handshapes [leba], but the spellings differ by the usage of a diacritic mark. This diacritic is used to mark which of the two hands is placed at the location spelled at the end of the initial sign segment. Namely, in row i the dominant hand [le] is placed at the location [fje]. In row iii, the non-dominant hand [ba] is placed at the location [lj]. In row v, the dominant hand [le] is placed at the location [pj]. The lack of a diacritic for the spelling in row v also indicates that both hands are active in the articulation of the ASL word.

Rows ii, iv, and vi describe the same kind of handedness and placement as is shown in rows i, iii, and v. That is to say, the spellings in rows ii, iv, and vi describe two-handed words, but only row iv places the non-dominant hand. The two-handedness is spelled differently for these rows, because the [ba] handshape is the same for both hands. For rows ii and iv, the spelling has been simplified by doubling the first handshape letter. In row vi, the spelling is simplified by only spelling the one [ba] handshape. For rows ii and iv, the diacritic mark is present when the dominant hand is placed and omitted when non-dominant hand is placed. In vi, the diacritic mark is never used since both hands are active and have the same handshape.

For both rows vi and vii, a single [ba] handshape is spelled, but row vi is two-hand and row vii is one-handed. The presence of the diacritic mark distinguishes row vii as a one-handed word, since the one hand is necessarily placed. By contrast, row vi does not have a diacritic mark, because both hands articulate together with the same handshape, making it ambiguous as to which is the dominant hand and which hand is placed.

1.3.2 Body locations

Locations are spelled with a combination of two to three letters corresponding to a location on the body or a location in space. The body is divided up into four main parts of the head, torso, arms, and legs. These main parts, by analogy to the six Cartesian directions, are assigned the characters: [i], [t], [j], and [k], respectively. These parts and their corresponding letters are illustrated in the following figure.

![Figure 11. Diagram of body parts and corresponding characters. Figure 11. Diagram of body parts and corresponding characters. Line-drawing of a human body, with dotted lines separating the body across the neck, from both armpits to corresponding shoulders, and across the waist. The head is labeled [i], the torso [t], both arms [j], and the hips and legs [k].](/static/main/word_structure/Figure_9.png)

For each main part of the body, additional letters are used to locate specific positions on a body part. The body part letter is written first, followed by the specific position letter. Please refer to the Body Locations page for more diagrams of body parts and specific locations.

An example

Let us again consider the ASL word lebatkitpj=a, glossed as example. This is a two-handed word with no dominance relationship between the hands, however, only one hand receives a location in the production of this word. In such words, the hand to be located corresponds with the signer's dominant hand by default. For this example, the location is spelled as [pj], which is the palm of the non-dominant hand, illustrated in the following diagram.

![Figure 12. Diagram of body location [pj] corresponding to the initial sign segment. Figure 12. Diagram of body location [pj] corresponding to the initial sign segment. The dominant hand (right-top, dark blue) corresponds to the drawing of the non-dominant hand with the palm labeled [pj] (left).](/static/main/word_structure/Figure_11.png)

By combining the location with the handshapes and palm orientations discussed in the previous sections, the initial sign segment is spelled as [lebatkitpj]. This is illustrated in the following diagram.

![Figure 13. Diagram of the initial sign segment for the ASL sign glossed example. Figure 13. Diagram of the initial sign segment for the ASL sign glossed example. The handshapes (left) show the dominant hand (top, red) and non-dominant hand (bottom, pink) and correspond to [leba]. The palm orientations (center) show the dominant hand (top, dark green) and non-dominant hand (bottom, light green) and correspond to [tkit]. The locations (left) show the dominant hand (top, dark blue) and non-dominant hand (bottom, light blue) and correspond to [pj].](/static/main/word_structure/Figure_12.png)

1.3.3 Spatial Locations

Some signs are described by locating the hands relative to their neutral space. We conceptualize neutral space as a volume of space in front of the body that a hand moves in by pivoting the arm at the elbow for angles less than or equal to 90 degrees between the upper arm and the forearm. Generally, when this angle exceeds 90 degrees or when the arm is held flexed at the shoulder, the hands are outside of their neutral space. Locations outside of the neutral space are used to describe the hands when they either begin articulating a word outside of their neutral space, or when the hands move outside of their neutral space as they articulate a word. The relative locations for the hands in the space outside of neutral space is illustrated in the following figure.

![Figure 14. Diagrams of natural locations viewed from the front (left) and above (right). Figure 14. Diagrams of natural locations viewed from the front (left) and above (right). Both are line-drawings of a human, from the waist up, with arms bent at the elbows in right angles and hands held with palms facing downwards. Vectors overlay on both hands with dotted perpendicular lines, showing the hands' location on the [i, k] and [j, t] axes in neutral space.](/static/main/word_structure/Figure_10.png)

Relative spatial locations are notated differently depending on the handedness of the words, or whether or not the two hands are located together. These relative spatial locations are again written using the six Cartesian direction letters, but now capitalized.

For instance, one-handed words can be located outside neutral space when they are semantically referring to a region of the body. Here, only the relative location of the dominant hand is spelled indicating that the hand is outside its neutral space. An example of this would be the ASL word glossed as mirror, which is articulated near the signer's face. In this word, the dominant [ba] hand begins with a relative location above its neutral space, spelled with the capitalized upward [I] character. The initial sign segment is then spelled as [báieI], and the entire word is written báieI-zsj.

Likewise, two-handed words can also be located outside of neutral space when they are semantically referring to a region of the body. The location of the hands outside their neutral space is described with a single capitalized letter. An example of this would be the ASL word glossed as worry, which is articulated near the head. Here, the location of the two hands [ba] are spelled with the capitalized upward [I] character. The initial sign segment is then spelled as [baitI], and the entire word is written as baitI~re.

A final example involves two-handed words where both hands are active in articulation, and both hands articulate in different relative locations outside of their neutral space. An example of this is the ASL word glossed as protect. Here, both hands share the same handshape and palm orientation, and the beginning of the word is spelled as [setk]. Since this word is articulated with the dominant hand at a relative location that is above the non-dominant hand, the dominant hand's location is spelled with capitalized upward [I], followed by the capitalized downward [K] for the non-dominant hand. Together, the initial sign segment is spelled as [setkIK], and the entire word is written as setkIK-a. This is illustrated in the figure below.

![Figure 15. Diagram of the initial sign segment for the ASL sign glossed protect. Figure 15. Diagram of the initial sign segment for the ASL sign glossed protect. The handshapes (left) show the dominant hand (top, red) and non-dominant hand (bottom, pink) and correspond to [se]. The palm orientations (center) show the dominant hand (top, dark green) and non-dominant hand (bottom, light green) and correspond to [tk]. The locations (left) show the dominant hand (top, dark blue) and non-dominant hand (bottom, light blue) and correspond to [IK].](/static/main/word_structure/Figure_13.png)

Locations as Inflection

While found more in signed discourse, the relative location of a word is sometimes inflected in a way that adds semantic detail or emphasis. The relative location of the hands would then be articulated outside their neutral space. An example of this would be the ASL word baat=t, glossed as small. If a signer were to inflect this word by articulating it with the hands very close together, the resulting word would have a meaning more related to a gloss like very small. In such a case, the inflection is spelled with the capitalized inward [T] character. The initial sign segment would then be spelled [baatT], and the entire word written as baatT=t. The following table shows examples of other instances of inflection shown by a difference of spatial location.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Inflected Form | Implied Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| baat=t | small | baatT=t | very small |

| baat-j | wide | baatJ-j | very wide |

| buáia=k | child | buáiaK=k | little child |

1.3.4 Multiple Locations

Signed words may be produced with hands that are located together, located on the body, or at relative locations outside of neutral space. The convention is to spell the hand locations first, then body locations, then the relative spatial locations. For example, consider the ASL word glossed as telescope. This two-handed sign has a dominance relationship, wherein only the dominant hand moves. Here, the dominant hand is located on ulnar edge of the passive hand [dj], and together they are located over the eye [qi]. All together, the sign is written as bbćitdjqi-a. The following table lists more examples of multiple locations for one-handed and two-handed words.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bbćitdjqi-a | telescope | two | dominant | Active |

2. The Action Segment

In the previous section, many examples were provided to explain the spelling conventions of the initial sign segment. In this section, we focus on the spelling of the action segment, which describes only those features of the initial sign segment that change. These changes are either internal motions that affect the handshape and/or palm orientation, or external motions that affect the body and/or spatial location, which can be singular (infrequent) or repetitive (frequent) motions.

For two-handed words, motions may be more complex. The hands can move in the same direction, or in different directions. They can move in unison (in phase) or in opposition (out of phase). Each one of these qualities affects the appearance and thereby the meaning of a signed word.

The spelling of the action segment occurs in two parts, which is diagramed in the following figure.

![Figure 16. Diagram of the action segment, with the descriptor (pink) and motion (gold). Figure 16. Diagram of the action segment, with the descriptor (left, pink) and motion (right, gold). The descriptors [-, =, ~] are listed below, and the motion is described as the motion of the hands and a change in sign.](/static/main/word_structure/Figure_20.png)

The first part (pink) consists of the action descriptor, which describes the frequency and symmetry of the motion. The second part (gold) is the change in sign, and spells out whether the motion is internal or external; and whether or not the movement is in unison (in phase). The action segment always describes the movement of the dominant hand, but for some two-handed words both hands move together. The condition for whether or not the action segment applies to the non-dominant hand is encoded in the spelling of the handshapes in the initial sign segment. Please refer to section 1.3.1 for that explanation.

For the rest of section 2, we focus on words that have a single action segment and address each type of change and motion individually. Words with multiple action segments stem from these and are more complex. Multiple action segments are addressed separately in section 3 of this page.

2.1 The Action Descriptor

There are three action descriptors the dash [-], double-dash [=], and the tilde [~].

The dash [-] descriptor is used to describe a motion that is articulated once in a word. An example would be the ASL word bcóie-oi, glossed as eat. In this word, the [-oi] motion occurs only once and describes the [bco] handshape of the dominant hand contacting the mouth. This [-oi] motion can be repeated (or reduplicated) to produce a new word. We describe the presence of this repetition with the double-dash [=] and change the spelling to bcóie=oi. This produces the following sequence:

With the change in spelling, the new word represents a change in meaning and would be glossed as food.

Another example would be the ASL word hhéak-fuj, glossed as sit. With repetition, the spelling becomes hhéak=fuj and would be glossed as chair with the following sequence:

The exact articulation of the double-dash [=] varies based on a signer's idiolect, and we refer the reader to see the work of Supalla and Newport (1978) for a deeper discussion. To compare the articulation of the double-dash to other features in this writing system, we will now conceptualize the [=] as a complete reduplication of the dashed spelling.

By comparison to the double-dash, the tilde [~] action descriptor describes a different kind of repetition. This descriptor is used only in two-handed words where both hands are active in the motion. When the motion of the hands repeats by mirroring half of the motion across the sagittal plane of the signer's body in the second reduplication, then the tilde [~] action descriptor is used to describe that symmetry.

Consider, for example, the ASL word sfata~re, glossed as science. The first half of the word may be articulated as sfata-rej/ret with left-handed signing. The second half of the word is then articulated in the same way as sfata-rej/ret, but with right-handed signing. The diagram below illustrates the sequence of articulation. (For a discussion on the [/] in this system, see section 2.2.2, Unified Inverse Motion.)

Another way to understand the articulation is by standing in front of a mirror. If one were to articulate sfata-rej/ret either left or right-handed, then they would see in the mirror sfata-rej/ret articulated right or left-handed, respectively. In other words, the combined repetition of articulating sfata-rej/ret (left-handed), and again (right-handed) produces the single word sfata~re.

Another example would be the ALS word foat~a'e, glossed as describe. This word may be separated into a repetition of foat-a/e as in the following diagram. (For a discussion on the ['] in this system, see section 2.2.1, Reciprocating Motion.)

Unlike the double-dash, the repeating signs that the tilde describes are not identical in production. They are instead mirror images of each other. For the examples in the preceding diagram, those mirror images were made apparent by their prose descriptions. To read more about how mirroring is handled in this writing system, please refer to the Sentence Structure page.

2.2 External Hand Motion

External motions change the location of the hands. We describe two kinds: linear motion, and rotational motion. Linear motion describes the hands moving along a straight line relative to the body, and rotational motion describes the hands rotating about an axis relative to the body. Both motions are spelled using the same six Cartesian direction letters (refer to sections 1.2 and 1.3). As before, horizontal axes are described with the parallel letter pairs [a, e] and [j, t], and the vertical axes are described with the parallel letter pair [i, k].

2.2.1 Linear Motion

Linear motion refers to movement of a hand along a single axis. This kind of movement is spelled with one lowercase letter, which represents a hand's direction of travel. For example, consider the ASL word glossed as show. This is a two-handed word with both hands active. The hands have two different handshapes [le, ba] and palm orientations [tk, it]. The signer's dominant hand has a location on the non-dominant hand [pj], and the two hands have a single unified outward [-a] motion from the signer's body while maintaining contact with each other. The [-a] is singular and linear, moving along a straight path. The complete spelling is lebatkitpj-a.

The simplest spelling occurs in one-handed signs. Consider the ASL word glossed as good. The non-dominant hand is inactive. The dominant [ba] hand begins at the chin [ui] location and moves outward in a single [-a] motion, again breaking contact with the body. The word is then written as báieui-a-pj.

In two-handed signs where only the dominant hand is active and both hands begin in contact, linear motion breaks that contact to articulate the word. An example of this is the ASL word glossed as develop. Here, the [be, ba] hands are initially in contact at the [pj] location. The dominant hand then moves upward in a single [-i] motion. The word is then written as bébaiaitpj-i.

The following table lists more examples of linear motion for one-handed and two-handed words.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| yláakI-a | fly | one | dominant | Inactive |

| yláakI=a | airplane | one | dominant | Inactive |

| báieui-a-pj | good | one | dominant | Inactive |

| bébaiaitpj-i | develop | two | dominant | Inactive |

| sfaakfj-a | continue | two | dominant | Active |

Diagonal Motion

Diagonal motion refers to simultaneous motion of a hand along two axes. This kind of movement is spelled differently using a pair of directional letters that are not parallel. They are spelled with an apostrophe ['] separating them. The apostrophe is used to describe in the spelling the two simultaneous directions of travel.

For example, consider the ASL word glossed as shout. This is a one-handed word with the dominant hand [bcati] moving forward [a] and upward [i] simultaneously from the signer's throat [ut]. The combined singular forward-upward motion is spelled [-a'i], which describes the resulting diagonal path. The complete word is written bcátiut-a'i. The following table lists more examples of diagonal motion for one-handed and two-handed words.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| béat-t'k | slash | one | dominant | Inactive |

| bcátiut-a'i | shout | one | dominant | Inactive |

| bbéatakbj-j'k | slope | two | dominant | Inactive |

| beitfj-j'k | roof | two | dominant | Active |

Reciprocating Motion

An apostrophe placed between a parallel pair of directions describes a repeated motion of a hand moving back and forth along these directions. We refer to this as reciprocating motion. An example is the ASL word glossed as similar. This is a one-handed word where the dominant [ya] hand repeatedly moves outwards sideways [j] then inwards sideways [t]. The combined reciprocating motion is spelled as [=j't], the complete word is written as [yáak=j't]. The following figure shows an animated diagram of the motion.

![Figure 17. Animated diagram of reciprocating linear motion. Figure 17. Animated diagram of reciprocating linear motion. Animated line-drawing of a human with arms bent at the elbows at right angles and hands held with palms oriented forwards and downwards. The hands are both shown to move inwards [t] and outwards [j] simultaneously.](/static/main/word_structure/reciprocating_motion.gif)

The following table lists more examples of reciprocating motion for one-handed and two-handed words.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| yáia=j't | similar | one | dominant | Inactive |

| llétkitfj=i'k | temperature | two | dominant | Inactive |

| foitatfje=a'e | relationship | two | dominant | Active |

| fcak~j't | behavior | two | dominant | Active |

2.2.2 Rotational Motion

Rotational motion refers to a hand moving along a closed curve. The path is often circular, and always occurs in a direction that is perpendicular to the rotation axis. Rotational motion is spelled with two letters, where the first letter is always [r] and the second letter corresponds to the axis of rotation.

Since articulating a rotation from the spelling may not be very intuitive for many readers, we will next describe a common method used to identify the axis of rotation called the "right-hand rule". This rule uses the [bfca] handshape depicted in the following figure.

![Figure 18. Diagram of the right-hand rule, displaying [ri]. Figure 18. Diagram of the right-hand rule, where the direction of rotation is determined by the axis of the thumb, displaying [ri]. A line-drawing of the right hand is shown with thumb extended upwards and all fingers partially flexed, forming a curve. An arrow points upwards [i] along the axis of the rotational plane, shown as a curved arrow labeled [r].](/static/main/word_structure/rhr_1.png)

The right-hand rule is used by articulating the [bfa] handshape, and then curling the fingers in the direction of rotation that that hand would undergo if rotating. As the hand takes the form of the [bfca] handshape, the thumb will point along the axis of rotation. For example, if the thumb points in the upward [i] direction, then the action segment is spelled [-ri]. The following figure illustrates an articulation of the movement [baak-ri] viewed from above.

![Figure 19. Animated diagram of rotational motion [ri]. Figure 19. Animated diagram of rotational motion [ri]. Animated line-drawing of a human with arms bent at the elbows at right angles and hands held with palms oriented forwards and downwards. The hands are both shown to rotate simultaneously.](/static/main/word_structure/rotational_motion.gif)

Free Motion and Continuous Contact

Free rotational motion occurs when the rotating hand is either not located or specifically located in space. As an example, consider the ASL word glossed as alone. This is also a one-handed sign where the signer's dominant [le] hand begins with the index finger pointed upwards. The signer then articulates a double rotation [=ri] about a vertical axis free within the neutral space of the dominant hand. The complete word is written as léie=ri. The following table lists more examples of free motion and continuous contact for one-handed and two-handed words.

Continuously contacting rotational motion occurs when the rotating hand is in contact with a part of the body, and the axis of rotation points into or away from the point of contact. As an example, consider the ASL word glossed as enjoy. This is a one-handed sign where the signer's dominant [ba] hand begins located on the chest [st] and articulates a single rotation about an axis pointed backwards into the chest [-re]. The complete word is written as bátest-re.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| luéak-ri | turn around | one | dominant | Inactive |

| léie-ri | always | one | dominant | Inactive |

| bátest-re | enjoy | one | dominant | Inactive |

| bátest=re | please | one | dominant | Inactive |

| ssáakaipj=ri | wash | two | dominant | Inactive |

| soit=ri | celebrattion | two | dominant | Active |

| saitni~rt | wash face | two | dominant | Active |

Momentary Contact

In the previous examples, the hands either rotate while in contact with a part of the body or freely within a neutral space. In these cases, when the hand(s) are in contact with the body, the hand(s) generally remain in contact through the whole articulation of the word. This is because the axis of rotation points into or away from the point of contact. However, there is another type of rotation that occurs when the axis neither points into or away from the point of contact. Signed words that possess these types of rotations are unique due to the momentary contact with the body that is produced.

An example would be the ASL word glossed as easy. This is a two-handed sign with the non-dominant hand inactive. The signer's dominant [ba] hand begins at the [fuj] location of the non-dominant hand then articulates a rotation such that the hand intermittently contacts that same location. The complete word is written as bábuaattifuj=ra.

The following table lists more examples of momentary contact for one-handed and two-handed words.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| béiani=re | beer | one | dominant | Inactive |

| bábuateaifuj=rt | easy | two | dominant | Inactive |

| yatkfuj=ra | butt heads | two | dominant | Active |

Unified Inverse Motion

Some signs are produced from an in-unison free rotation of the hands. An example is the ASL word [soit=ri], glossed as celebrate. For the articulation of this word, both hands freely rotate about a vertical axis in their neutral space.

Two-handed, in-unison motion of a single rotation axis only permits momentary contact as in the ASL word [yatkfuj=ra], glossed as butt heads. When the hands are both articulated in unison and continuously in contact, the motion is spelled with two rotations separated by a forward slash [/]. The forward slash implies that the rotation spelled before it is articulated by the dominant hand and the rotation spelled after it is articulated by the non-dominant hand. For continuous contact throughout the articulation, the second rotation must be the inverse of the first, and we say the motion is unified inverse.

Another example of unified inverse motion is the ASL word glossed as America. In this two-handed word the non-dominant hand is active. To articulate the word, the dominant hand rotates with an upward [ri] rotation, while the non-dominant hand simultaneously rotates with a downward [rk] rotation. The complete spelling of the word is then Fatefje=ri/rk.

The following table lists more examples of unified inverse motion.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| foitatfje=ri/rk | union | two | dominant | Active |

| Fatefje=ri/rk | America | two | dominant | Active |

| fluaak=ri/rk | audio recording | two | dominant | Active |

Opposed Inverse Motion

Two-handed signs may also be articulated with the hands in opposition to each other, as well as inverse. We refer to this motion as opposed inverse motion. For these kinds of words, both hands are active but cannot stay in contact, because they are not moving in unison. An example would be the ASL word glossed as mix. Here the dominant [fc] hand is held above the non-dominant [fc] hand. Both hands rotate in opposite directions in such a way that they momentarily pass over each other as they rotate. Both rotations are spelled with an apostrophe ['] between them, where the first rotation applies to the dominant hand and the second applies to the non-dominant hand. The following table lists more examples of opposed inverse motion.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fcakaiIK=ri'rk | mix | two | dominant | Active |

| sfatateIK=ri'rk | socialize | two | dominant | Active |

2.2.3 Partial Rotation

When the path of the hand follows a curve, we refer to this motion as a partial rotation since the curved path often has the appearance of a semi-circle or hop. Hops can occur along any rotational axis, but end in a linear direction that is perpendicular with that axis. For this reason, a hop is spelled as a rotation, but with a third letter that specifies the linear direction of its endpoint. As illustrated in the following figure, the rotational axis is pointed away from the signer spelled with [ra] and, since the hop is directed outward sideways along the [j] direction, the full spelling is [raj].

![Figure 20. Illustration of a hop, displaying [raj]. Figure 20. Illustration of a hop, displaying [raj]. Line-drawing of a human with arms bent at the elbows at right angles and hands held with palms oriented forwards and inwards. The left hand is shown to make a partial rotation, represented by a curved dotted line. The rotation is labeled as [ra] with a linear endpoint in an outwards direction [j].](/static/main/word_structure/raj.png)

As an example, consider the ASL word glossed as travel. This is a one-handed word in which the signer's dominant hand [vce] articulates a single hop, rotating partially about the [e] axis, but ending at a location higher [i] than it started. The partial rotation is then spelled as [-rei], and the complete word is written vcéak-rei. The following table lists more examples of partial rotations for one-handed and two-handed words.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| vcéak-rei | travel | one | dominant | Inactive |

| vcéak=rei | journey | one | dominant | Inactive |

| bbátepj-rta | next | two | dominant | Inactive |

| lueatfj-raj | opposite | two | dominant | Active |

Just as with the full rotations, partial rotations can also be articulated as a unified inverse motion. For example, consider the ASL word glossed as bring. This is a two-handed word with both hands active, and both [ba] hands begin at the side of the body outside their neutral space. The hands then hop in unison inward to their neutral space, with the dominant hand articulating [ret] and the non-dominant hand articulating [raj]. The complete word is then written baaiJT-ret/raj. The following table lists more examples of partial rotation as unified inverse motion.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| baai-ret/raj | bring | two | dominant | Active |

| baat=rej/rat | arrangement | two | dominant | Active |

2.2.4 Located Motion

Motion can be produced by simply changing the location of the hands. We refer to this as located motion. This motion is not necessarily linear or rotational, and its action segment is spelled with the final location. For instance, a word that begins its articulation without a location in its initial sign segment may move to a location by the end of the word. An example of this is the ASL word glossed as have. This is a two-handed word with both hands active in the handshape [bua]. The word is articulated with a straight movement of the hands to make singular contact with the chest [-ct]. This complete word is written buate-ct.

The following table lists more examples of located motion for one-handed and two-handed words.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bcóie-oi | eat | one | dominant | Inactive |

| bcóie=oi | food | one | dominant | Inactive |

| lábait-pj | forbid | two | dominant | Inactive |

| sséiatk=sj | work | two | dominant | Inactive |

| bbáieui-a-pj | good | two | dominant | Inactive |

| saat-pj | with | two | dominant | Active |

| yaak=fj | measure | two | dominant | Active |

| Fluafaat~pj | Jesus | two | dominant | Active |

2.3 Internal Hand Motion

Internal hand motion refers to motion that results from changes in the configuration of the hand(s), and is divided into three categories. We call these categories fine motion, changes in handshape, and changes in palm orientation. Fine motor skills are required to articulate the motions in each of these categories. Fingerspelling, for example, requires fine motor skills and is predominantly within the changes in handshape category, but not exclusively, since different letters of the manual alphabet require changes in palm orientation as well. In particular, the articulation of motions found in the fine motion category are very similar to those of both changes in handshape and changes in palm orientation, and so, it is important to define each category clearly.

The fine motion category contains those internal motions that place an emphasis on the motion, not the word-final configuration of the hands. By contrast, the changes in handshape category are those internal motions that place an emphasis on the handshape, and the changes in palm orientation category are those internal motions that place an emphasis on the palm orientation. By emphasis, we are broadly referring to a measure of transience observed of the postures within a word and refer the reader to the work of Johnson and Liddell (2011) for a deeper discussion. The emphasis used in each of these categories is reflected in the spelling for each kind of motion. In turn, it is the placement of emphasis that allows signers to recognize styles of signing, like fingerspelling, within discourse where linguistic variation could otherwise cause confusion.

A prime example may be the ASL word vúia-o, glossed as no. This word is derived from an older form with the same gloss, the ASL word huéia-bcó, which has the same meaning, but is a fingerspelling of the English word no. The newer form is articulated with a single pinching action of the dominant hand [vu], palm facing upwards and forwards from the signer. With knowledge of the older form, one may be inclined to use an alternate spelling vúia-vuó, which captures a similar articulation and spelling with the older form. Although, this alternate spelling would place the emphasis on the word-final handshape and not the motion. Thus, the [-o] spelling in the newer form is preferred since it places the emphasis on the motion, rather than a word-final handshape.

The distinction of fine motion may be made clearer by considering the ASL word bcóia-vlé, glossed as ok. This is also a one-handed word where the dominant hand [bco], palm oriented upwards and outwards, changes to the [vle] handshape. Writing this word as vcoia-c may capture a similar appearance, since this word is often articulated quickly. This ASL word is a direct borrowing that derives from fingerspelling the acronym of the English word okay. That being the case, it is more appropriate for the final handshape to be emphasized, rather than the motion used to produce it.

In the following subsections each of the three categories are discussed further, along with tables of examples.

2.3.1 Fine Motion

Fine motion refers to emphasized movement produced by the fingers and wrists. There are five letters used to describe fine motion: [z, u, x, c, o]. A fine movement is spelled with the part of the body that is moving, where the first letter in the sequence is one of these fine motion letters.

For example, the wiggling of the fingers and wrists is spelled with [zfj, zsj], respectively. The bending of the fingers and wrists is then spelled with [ufj, usj], respectively. The flexing of the fingers is spelled with [xfj]. Flicking can be spelled on its own as [c] or used in combination with the fingers flicking off a point as [cfj]. Pinching, too, can be spelled by itself as [o], or spelled after a [z] (e.g., [zo]). The following figures show basic animations of these movements.

![Figure 21. Wiggling action [-zfj]. Figure 21. Wiggling action [-zfj]. Animated drawing of the left hand in the handshape [fa], with all fingers flexing each of their first knuckles in a repeated sequence.](/static/main/word_structure/fa_zfj.gif)

![Figure 22. Bending action [-ufj]. Figure 22. Bending action [-ufj]. Animated drawing of the left hand in the handshape [ba], with all fingers flexing their first knuckles simultaneously.](/static/main/word_structure/ba_u.gif)

![Figure 23. Flexing action [-xfj]. Figure 23. Flexing action [-xfj]. Animated drawing of the left hand in the handshape [fa], with all fingers flexing their second and third knuckles simultaneously.](/static/main/word_structure/fa_xfj.gif)

![Figure 24. Pinching action [-o]. Figure 24. Pinching action [-o]. Animated drawing of the left hand in the handshape [lsc], with index finger and thumb partially flexing all knuckles simultaneously, touching their two pads together.](/static/main/word_structure/lce_o.gif)

![Figure 25. Flicking action [-c]. Figure 25. Flicking action [-c]. Animated drawing of the left hand in the handshape [so], with index finger flexed, the thumb is extended and in contact with the radial edge of the index finger, then releases contact through abduction.](/static/main/word_structure/so_c.gif)

![Figure 26. Flicking action [-usj]. Figure 26. Bending action [-usj]. Animated drawing of the left hand in the handshape [ba], with the hand bending at the wrist.](/static/main/word_structure/usj.gif)

![Figure 27. Wiggling action [-zsj]. Figure 27. Wiggling action [-zsj]. Animated drawing of the left hand in the handshape [fa], with the wrist wiggling radialy](/static/main/word_structure/zsj.gif)

![Figure 28. Wiggling action [-zo]. Figure 28. Wiggling action [-zo]. Animated drawing of the left hand in the handshape [lco], with the index finger in contact with the thumb, and the thumb wiggling.](/static/main/word_structure/zo.gif)

![Figure 29. Flicking action [-c]. Figure 29. Flicking action [-c]. Animated drawing of the left hand in the handshape [lco], with index finger and thumb flexed, the index finger is in contact with the thumb, then releases contact through extention.](/static/main/word_structure/lco_c.gif)

Wiggling

We consider wiggling to be a subtle, not necessarily organized, motion that may look like vibration or shaking when articulation is minimal. The spelling of a wiggling motion starts with the letter [z], followed by the spelling of the part of the body that performs the wiggling.

An example of wiggling is found in the ASL word glossed as boil. This is a two-handed word in which the non-dominant hand is inactive. The hands take two different handshapes [fua] and [ba], respectively. The dominant hand is held with the palm forwards and upwards [ai] below the non-dominant hand, which is held with the palm inwards and downwards [tk]. A wiggling of the fingers spelled [zfj] is articulated, which depicts fire heating a surface. For this word, the wiggling of the fingers is clearly articulated. The word is then written fuábaaitkKI-zfj.

When the wiggling motion is at a minimum, the apparent vibration of the hand(s) no longer has a distinct location and, in many cases, may be articulated from the arms or wrists. An example of this is the ASL word glossed as meat. This is a two-handed word with both hands active, where the fingers of the dominant hand [fsu] grasp the radial edge of the non-dominant hand [fa]. Together, both hands shake slightly to emphasize the point of contact (i.e., the meat of the hand). The whole word is written fsufaaktebj-z.

The following table lists more examples of wiggling for one-handed and two-handed words with [z] in their spelling.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fáieui-zfj | color | one | dominant | Inactive |

| fábatkat-zfj | study | two | dominant | Inactive |

| fuaai-zfj | wait | two | dominant | Active |

| fsufaaktebj-z | meat | two | dominant | Active |

Bending

We consider bending to be an overt motion that clearly folds the body at a specific joint. The spelling of a bending motion starts with the letter [u]. An example of this is in the ASL word glossed as yes. This is a one-handed word where bending occurs at the wrist and is spelled [usj]. The hands [se], palms forwards and downwards, bend at the wrist twice. The whole word is written seak=usj.

The following table lists more examples of bending for one-handed and two-handed words with [u] in their spelling.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| báak=usj | late | one | dominant | Inactive |

| séia=usj | yes | one | dominant | Inactive |

| vébatkatpj-usj | read | two | dominant | Inactive |

| buait-ufj | expect | two | dominant | Active |

| buait=ufj | hope | two | dominant | Active |

| baak~usj | walk | two | dominant | Active |

Flexing

We refer to flexing as a flexion of one or more knuckles of the fingers and/or thumbs. A flexing motion is spelled beginning with the letter [x]. An example of flexing is the ASL word glossed as who. This is one-handed word where the dominant hand [lfa] is in contact with the chin [ui] via the fully extended thumb. The word is then articulated with a flexing of the index finger [xfj]. The complete word is written lfáitui=xfj.

The following table lists more examples of flexing for one-handed and two-handed words with [x] in their spelling.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| léia-xfj | ask | one | dominant | Inactive |

| lfáitui=xfj | who | one | dominant | Inactive |

| bćitoi=x | orange | one | dominant | Inactive |

| leia=xfj | test | two | dominant | Active |

Flicking

We refer to flicking as the motion produced when the curled or bent fingers suddenly break contact with the thumb or another part of the body. A flicking motion is spelled beginning with the letter [c]. This means that, if the flicking action is off of the thumb, then the handshape of the active hand(s) must be spelled with the letter [o]. If the thumb is not involved then the active hand(s) must be spelled with a [u] or [c] and located on the body. An example is the ASL word glossed as light. This is a one-handed word where the dominant hand [flco] makes contact with the chin [ui]. The flicking motion is articulated with the curled middle finger of the [flco] handshape, suddenly and repeatedly breaking contact with the thumb. Since the dominant hand is placed at the chin with the palm facing it, the flicking motion strikes the chin. The complete word is written flcóieui=c.

The following table lists more examples of flicking for one-handed and two-handed words with [c] in their spelling.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lcóieI-c | understand | one | dominant | Inactive |

| flcóieui=c | light | one | dominant | Inactive |

| hcóseatsj-c | beat | two | dominant | Inactive |

| flcóseaksj=c | melon | two | dominant | Inactive |

| lcoitqi-c | surprise | two | dominant | Active |

| flcoit-c | awful | two | dominant | Active |

Pinching

We refer to pinching as the bent or curled fingers contacting the thumb. A pinching motion is spelled beginning with the letter [o]. This implies that the handshape of the hand performing the action must be spelled with one of the two letters [c, u]. An example of pinching can be seen in the ASL word glossed as bird. This is a one-handed word where the dominant [lu] hand is located at the mouth with the palm upwards and forwards from the signer. Then the index finger and thumb of the dominant hand articulate a pinching motion, such that they repeatedly come together, depicting a birds beak opening and closing. The complete word is written lúiaoi=o.

The following table lists more examples of pinching for one-handed and two-handed words with [o] in their spelling.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| vúia-o | no | one | dominant | Inactive |

| lúiaoi=o | bird | one | dominant | Inactive |

| búbaiaakfuj-o | deflate | two | dominant | Inactive |

2.3.2 Changes in Handshape

A change in handshape produces a motion that emphasizes the final configuration of the fingers and thumb at the end of a word. That change is then spelled with the word-final handshape.

An example of this is the ASL word glossed as microwave. This is a two-handed word in which both hands are active. Both hands begin in the [se] handshape with palms inwards and backwards [te] in relation to the body. Then, in the action segment, the hands change to the [fe] handshape. The fingers, pointing towards each other, depict radiation directed into within an oven. The complete word is written sete-fe.

The following table lists more examples of handshape changes for one-handed and two-handed words.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bcóia-vlé | okay | one | dominant | Inactive |

| sete-fe | microwave | two | dominant | Active |

| seit=fa | sign | two | dominant | Active |

2.3.3 Changes in Orientation

A change in palm orientation produces a motion that emphasizes the final orientation of the palm(s) at the end of the word. That change is then spelled with the palm orientation(s) that changed.

An example of this is in the ASL word glossed as finish. This is a two-handed word in which both hands are active. Both hands [fa] begin with the palms oriented upwards and backwards in relation to the body [ie]. Then, in the action segment of the word, the hands' palm orientations change to point upwards and forwards from the body [ia]. The complete word is written faie-ia.

The following table lists more examples of palm orientation changes for one-handed and two-handed words.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| léia-ie | first | one | dominant | Inactive |

| lxétani=tk | apple | one | dominant | Inactive |

| lébatkatfje-te | start | two | dominant | Inactive |

| sóbatkatpj=te | key | two | dominant | Inactive |

| faie-ia | finish | two | dominant | Active |

| bcaia~ie | compare | two | dominant | Active |

2.3.4 Combinations

Since changes in handshape and palm orientation both place emphasis on the final configuration of a word, their spellings follow the same rules for the initial sign segment. These changes are spelled in the same order as in the initial sign segment when they co-occur.

An example is the ASL word glossed as oxygen. This is a one-handed word where the handshape [bco] changes to [ve] as the wrist changes the palm orientation from [it] to [ie]. The complete word is written bcóit-véie.

The following table lists more examples of co-occurring handshape and palm orientation changes.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bcóit-véia | oxygen | one | dominant | Inactive |

| lúat-bcóia | go | one | dominant | Inactive |

3. Multiple Actions

In section 2, the various types of spellings for words with a single action segment were discussed. We will now turn our attention to words spelled with multiple action segments. These words are distinct in that they contain more than one action descriptor in their spelling. In this section we do not cover every type of multiple action that is observed, but we do provide a brief description of our spelling conventions for common articulation patterns, enough so that readers may be able to determine a spelling for those articulation patterns not listed. In doing so, we have broadly organized these patterns into six groups, each with a table of examples in which each example shares a similar spelling with others of the same group.

3.1 Fingerspelling

Fingerspelling refers to the signed use of a manual alphabet, for which a set of unique handshapes palm orientations, and locations correspond to a written letter of a spoken language's writing system. For instance, the ASL manual alphabet maps different handshape and palm orientation pairs to the English alphabet. Signers then can articulate English words letter by letter through a sequence of those pairs. Since the average number of characters in an English word is five, fingerspelled words are therefore identifiable as having an average of four action segments when spelled in our system.

The following table provides corresponding ASL spellings of the letters in the English manual alphabet. These spellings are based on forms found in our source materials. To view the animated handshapes corresponding to the English alphabet, please see our ASL Manual Alphabet page.

English Manual Alphabet

In their isolated forms, several of our sources stipulate a hyper-articulation for the English letters M, N, and T that would be spelled as [sméia-z, shéia-z, sléia-z], respectively, with the fingers flexed around the thumb. Likewise, the English letter F might be articulated as [bséia-z] with the fingers closed and the index finger tightly flexed. These hyper-articulations are likely more recognizable to some signers. However, as with any language, the true form of articulation for each letter will vary depending on the phonetic environment, the type of discourse, and dialect of the signer.

It is also common to articulate English words with the inactive non-dominant handshape [le] placed at the wrist of the dominant hand, so as to draw attention to it. For example, the English word the when fingerspelled in ASL may be written as luéia-huéat-bxéia. Though, with the non-dominant handshape [le] placed at the wrist, the word is then written two-handed as lueléiatesuj-huéat-bxéia. The following table lists more examples of fingerspelling with the ASL manual alphabet.

| ASL Articulation | English Word | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| luéia-huéat-bxéia | the | one | dominant | Inactive |

| lútk-héia-yé-bć-vlé | quick | one | dominant | Inactive |

| béia-hré-bcó-wé-hué | brown | one | dominant | Inactive |

| fóia-bcó-lxé | fox | one | dominant | Inactive |

| yéia-te-héia-mué-vléak-séia | jumps | one | dominant | Inactive |

| bcóia-vé-bxé-hré | over | one | dominant | Inactive |

| láia-sá-lué-j-t'k-j-yá | lazy | one | dominant | Inactive |

| lóia-bcó-lúat | dog | one | dominant | Inactive |

3.2 Drawing

When signing about abstract shapes, the hands can be used to draw the outline of those shapes, and we refer to this as drawing. The resulting sequence of articulation may be quite complex, especially when that shape outlines the path or behavior of an object. To write them, they would appear as a sequence of multiple action segments. While these forms may be largely contextual and dynamic in articulation, some are regular and frequent enough to be ascribed distinct meanings. It is these types of regular forms that exemplify this group.

As an example, consider the ASL word glossed as square. This is a two-handed word with both hands active, and where its articulation draws the outline of a square. The index finger of both [lue] handshapes begin in contact and move outwards sideways from each other, then downwards, and finally come back together in contact.

For more abstract shapes, the sequence of "move outwards sideways from each other, then downwards" (spelled [-j-k]) could be extended to a longer sequence of motions to suit the needs of the signer. The following table lists more examples of regular forms of drawing written as one-handed and two-handed words.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lueiafj-j-k-fj | square | two | dominant | Active |

| lueiafj-j'k-fj | triangle | two | dominant | Active |

| lluéiafj-i-j'k-fj | right triangle | two | dominant | Inactive |

3.3 Tapping

Words in this group are articulated with a tapping motion that either contacts the body momentarily at different body locations or appears to tap in multiple spatial locations.

For example, consider the ASL word léia-oi-gi, glossed as deaf. This one-handed word, with the palm oriented upwards and forwards from the signer, is articulated with the dominant [le] hand. The index finger in this handshape taps first near the mouth, and then near the ear.

To contrast, consider the ASL word héat-k-raj, glossed as hard-of-hearing. This, too, is a one-handed word where the dominant [he] hand articulates a downwards motion, as the first tap. The hand then hops once in a partial rotation that ends outwards to the signer's side, as the second tap. For this word, the tapping of the two different spatial locations is implicit and are reflected in the directional spelling of the motion. The following table lists more examples of tapping for one-handed and two-handed words.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bate-ct-gt | body | two | dominant | Active |

| bcóit-oi-ni | home | one | dominant | Inactive |

| léia-gi-itoi | deaf | one | dominant | Inactive |

| héat-k-raj | hard of hearing | one | dominant | Inactive |

3.4 Swiping

Words in this group are articulated with a swiping motion that swipes past a location on the body. In other words, while a hand is moving it makes momentary contact with another location on the body. This kind of motion can be recognized by the lack of a body location written in the initial sign segment. Instead, a body location is written as the first action segment, followed by a second action segment characterized by a linear motion.

For example, consider the ASL word glossed as last. This is a two-handed word in which only the dominant hand is active. While moving downward, the pinky finger of the dominant handshape [ye] makes momentary contact with the pinky finger of the non-dominant handshape [ye] and continues in the same direction of travel. This action segment of this word is written with a body location followed by a linear motion [-fj-k]. The complete word is then written as yyéatte-fj-k. The following table lists more examples of swiping.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| buábaktti-pj-t | new | two | dominant | Inactive |

| sséat=lébj-a | yearly | two | dominant | Inactive |

| yyéatte-fj-k | last | two | dominant | Inactive |

3.5 Bounded Rotations

Words in this group are unique in that they are articulated with a rotating motion prior to contacting the body. We refer to these as bound rotations, such that the first action segment of a rotation is followed by a second action segment that is characterized by a body location.

A first example is the ASL word sséak-rt-iasj, glossed as lock. This is a two-handed word in which only the dominant hand is active. Here, both hands [se] begin with the palms oriented forwards and downwards. The dominant hand then rotates while changing the palm orientation to upwards and backwards, then contacts the wrist of the non-dominant hand. The convention here is that the rotation is small and relatively near to the word-final point of contact.

In contrast, consider the ASL word ssétebj-rt-pj, glossed as year. Here, the two hands [se] begin together, with dominant hand located on the radial edge of the non-dominant hand [bj]. Then the dominant hand rotates, making word-final contact in the same location at the start of the word. By comparison to that in the first example, the rotation in this word is larger.

Another spelling convention is seen for the ASL word weatbj~rt-bj, glossed as world. This is similar to the second example in that both hands [we] begin together, with the dominant hand located on the radial edge of the non-dominant hand [bj]. This example differs, however, in that the two hands then articulate a mirrored rotation around one another, ending in contact at the same word-initial location [bj]. Likewise, by comparison, the rotation produced in this word would be of a similar size to that in the second example. The following table lists more examples of bounded rotation.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sséak-rt-aisj | lock | two | dominant | Inactive |

| sséatbj-rt-bj | year | two | dominant | Inactive |

| weatbj~rt-bj | world | two | dominant | Active |

3.6 Oscillating Directional Motion

Words in this group are articulated with a sequence of two types of motion that appear to be simultaneous. The first motion is small and repetitive, often distinguished as repetitive internal motion or external reciprocating motion, while the other motion is larger and less frequent by comparison, characterized as linear motion or located motion. Together, the hand(s) appears to oscillate in a single direction, and we refer to this as oscillating directional motion.

Oscillating directional motion is spelled with a sequence of at least two action segments. A basic example of this is the ASL word vcéiaoi=j't-a, glossed as snake, which depicts the motion of a snake. Here, the dominant [vce] hand, palm oriented upwards and forwards from the signer, begins in contact with the mouth. Then, a repeated sideways outwards-inwards reciprocating motion [=j't] is articulated simultaneously with the hand traveling in a single forwards linear motion [-a]. The following table lists more examples of oscillating directions for one-handed and two-handed words.

| ASL Word | Gloss | Handedness | Placement | Non-Dom. Hand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| vxéiaoi=j't-a | snake | one | dominant | Inactive |

| lfaakfja-zsj-j | language | two | dominant | Active |

| lueia~i'k-j | variation | two | dominant | Active |

4 Glossary of Terms

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| action descriptor | one of three characters that describe the frequency and symmetry of the hand motion

§2 |

| action sign segment | the word-final letters that describe how the articulation of a word evolves to its end

Intro., §2 |

| arms | the arms of the body including the shoulders and hands

§1.3.2 |

| bending | an overt motion that clearly folds the body at a specific joint or joints

§2.3.1 |

| bounded rotations | a hand motion that contacts the body after a rotation of that hand

§3.5 |

| change in handshape | the motion that emphasizes the final configuration of the fingers and thumb at the end of a word

§2.3.2 |

| change in palm orientation | the motion that emphasizes the final orientation of the palm(s) at the end of the word

§2.3.3 |

| change in sign | the word-final sequence of letters describing the motion of the hands as being internal, external, or whether the movement is in unison (in phase)

§2 |

| continuously contacting rotational motion | motion of the hands that is in contact with a part of the body, and the axis of rotation points into or away from the point of contact

§2.2.2 |

| dash | an action descriptor describing singular motion of the hands

§2.1 |

| diagonal motion | motion of the hands moving along a straight line relative to the body moving simultaneously along two axes

§2.2.1 |

| dominant hand | the hand (right or left) that a person tends to favor when performing certain activities

Intro. |

| double-dash | an action descriptor describing repeated (or reduplicated) motion of the hands

§2.1 |

| drawing | a motion of the hands used to draw the outline of shapes

§3.2 |

| emphasis | a measure of transience observed of the postures within a word

§2.3 |

| external motion | hand motion that affects the body and/or spatial location of the hands

§2 |

| fine motion | emphasized movement of the hands produced by the fingers and wrists

§2.3, §2.3.1 |

| fingerspelling | the signed use of a manual alphabet, for which a set of unique handshapes palm orientations, and locations correspond to a written letter of a spoken language's writing system

§3.1 |

| flexing | a flexion of one or more knuckles of the fingers and/or thumbs

§2.3.1 |

| flicking | the motion produced when the curled or bent fingers suddenly break contact with the thumb or another part of the body

§2.3.1 |

| free rotational motion | motion of the hands that is either not located or located specifically in space and not on the body

§2.2.2 |

| handedness | the number of hands used to produce a signed word

Intro., §1.3.1 |

| handshape | the hand's configuration of the fingers and thumb

§1.1 |

| head | the head of the body excluding the neck

§1.3.2 |

| initial sign segment | the word-initial letters that describe how a word begins its articulation

Intro., §1 |

| internal motion | hand motion that affects the handshape and/or palm orientation of the hands

§2 |

| legs | the legs of the body including the region just below the waist

§1.3.2 |

| linear motion | motion of the hands moving along a straight line relative to the body along a single axis

§2.2, §2.2.1 |

| located motion | motion of the hands produced by changing the location of the hands

§2.2.4 |

| momentary contact | motion of the hands that momentarily and periodically contacts a part of the body, originating from rotational motion having an axis that does not point into or away from the point of contact

§2.2.2 |